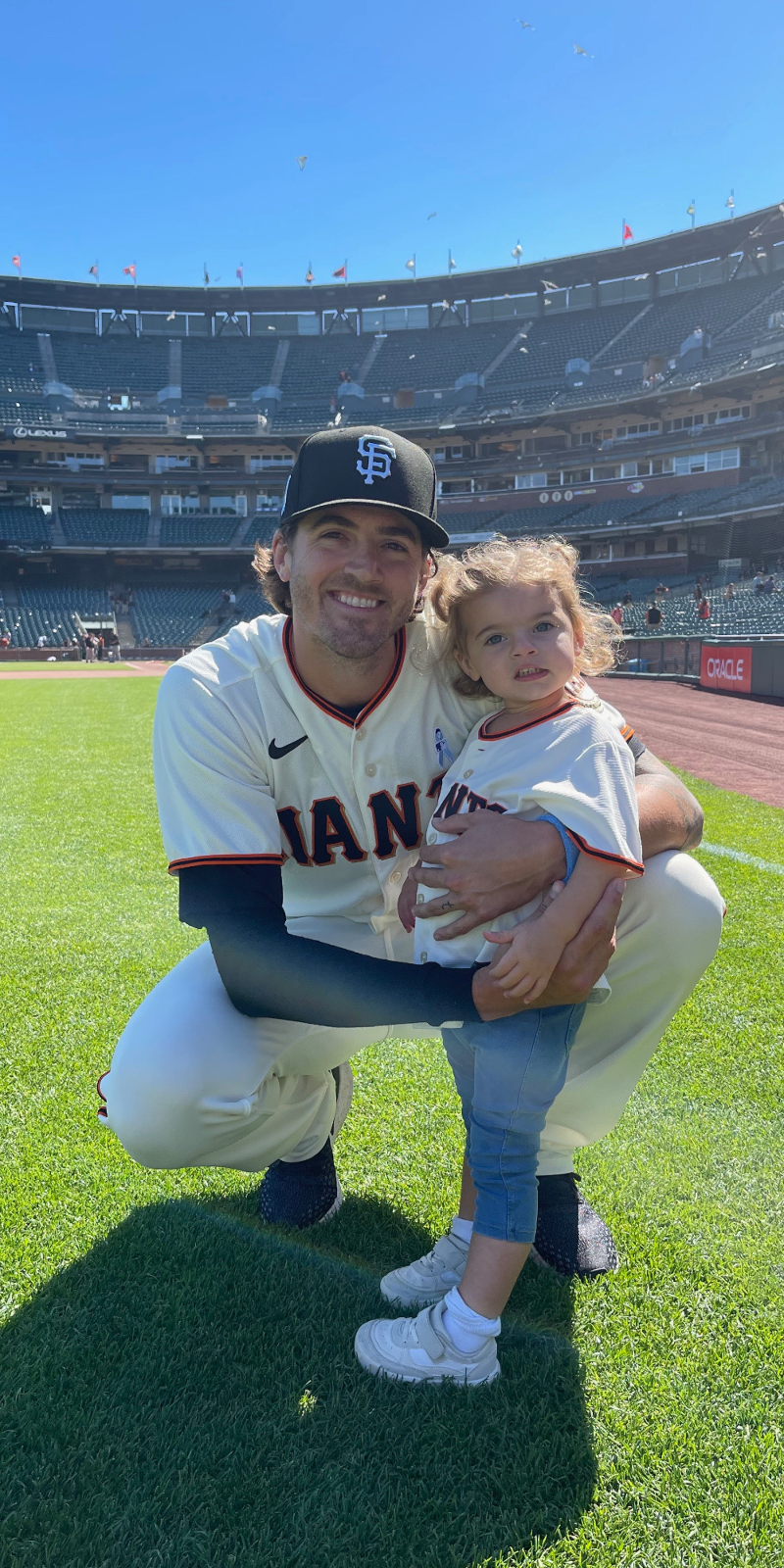

On the mound, he’s all limbs and ease. There is a focus but not an apparent fire; there is a calm that belies the moment, an even-keel that could blur the Baltimore and San Francisco versions.

How is Kevin Gausman performing? You wouldn’t know by looking at a pitcher who is light on fist-pumps and fury.

To approach the inner competitor, the one who might wear more emotion on his sleeve, give him a jersey that doesn’t require them.

High school basketball brought out another Gausman, one who played with more outward emotion with Grandview High School in Colorado, one who faced off with down-the-road rival Cherokee Trail in early 2010, his senior year, and stole the ball from the opposing point guard in the last minute.

Gausman, all 6-foot-2 and maybe 160 pounds of him, had a breakaway, a lead and thoughts of a gym-rocking dunk. But that point guard had not given up on the play and “just leveled my lower half.”

“He took me out. It was kind of a dirty play,” Gausman said.

“It was a nasty, nasty, cheap shot,” then Grandview head baseball coach Dean Adams said.

He was sent crashing past the hoop. Sure, Gausman was mad, but, “My brother didn’t really react,” Brian Gausman said.

Grandview Baseball, meanwhile, was furious. Adams had been standing at the end of the gym and rushed on to the court to yell at the offender. As pushing and shoving commenced between the two teams, Gausman’s baseball teammates spilled onto the floor, too. Gausman got back to his feet and joined the yelling, and the game had to be called early because of the commotion.

“I wasn’t going to stand for that bullcrap,” said Adams, who was protecting his ace but said he would do the same for any of his players.

The most public fight of Gausman’s young life entailed his getting upended, his going down and bouncing back up, and his friends swarming to his defense. He was not the aggressor and did not need or try to throw a punch; he has induced many more poor swings than he’s thrown himself.

To reach the top — and the All-Star, who has made a strong case that he is the best pitcher on the planet not named Jacob deGrom, indeed has the penthouse view — you need to know when not to blow up. Through a career that has seen him become the fourth-overall pick, grasp at a potential that always seemed out of the reach with the Orioles, ping-ping across a few teams before getting designated for assignment by Cincinnati, Gausman has tried to remain as steady as his on-the-rubber demeanor. It has been a roller-coaster, but not one with screams. Each high and, especially, low has taught him something. He takes the lesson, he keeps his head and he keeps riding.

“I never get that upset,” Gausman told KNBR this weekend. “Being a starting pitcher, you have to have a short memory, so I think that’s definitely helped. Getting beat around as much as I did early in my career, I think being able to forget it definitely helped.”

The climb up

To reach the zenith, you have to have more than a cool demeanor. You have to grow.

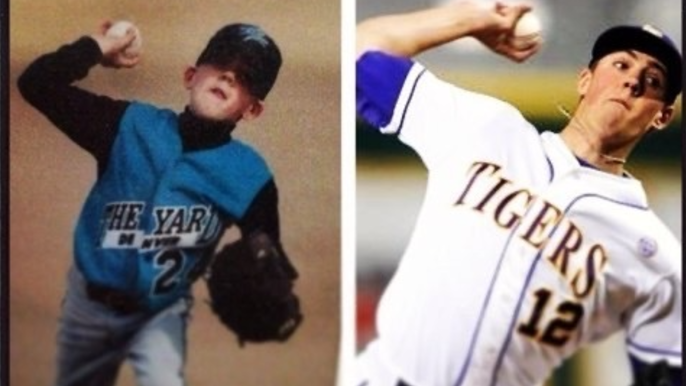

Kevin gravitated toward baseball because he gravitated toward Brian, seven years his elder and a baseball star in his own right, All-State at Grandview before stops at New Mexico State and briefly in the Royals’ system.

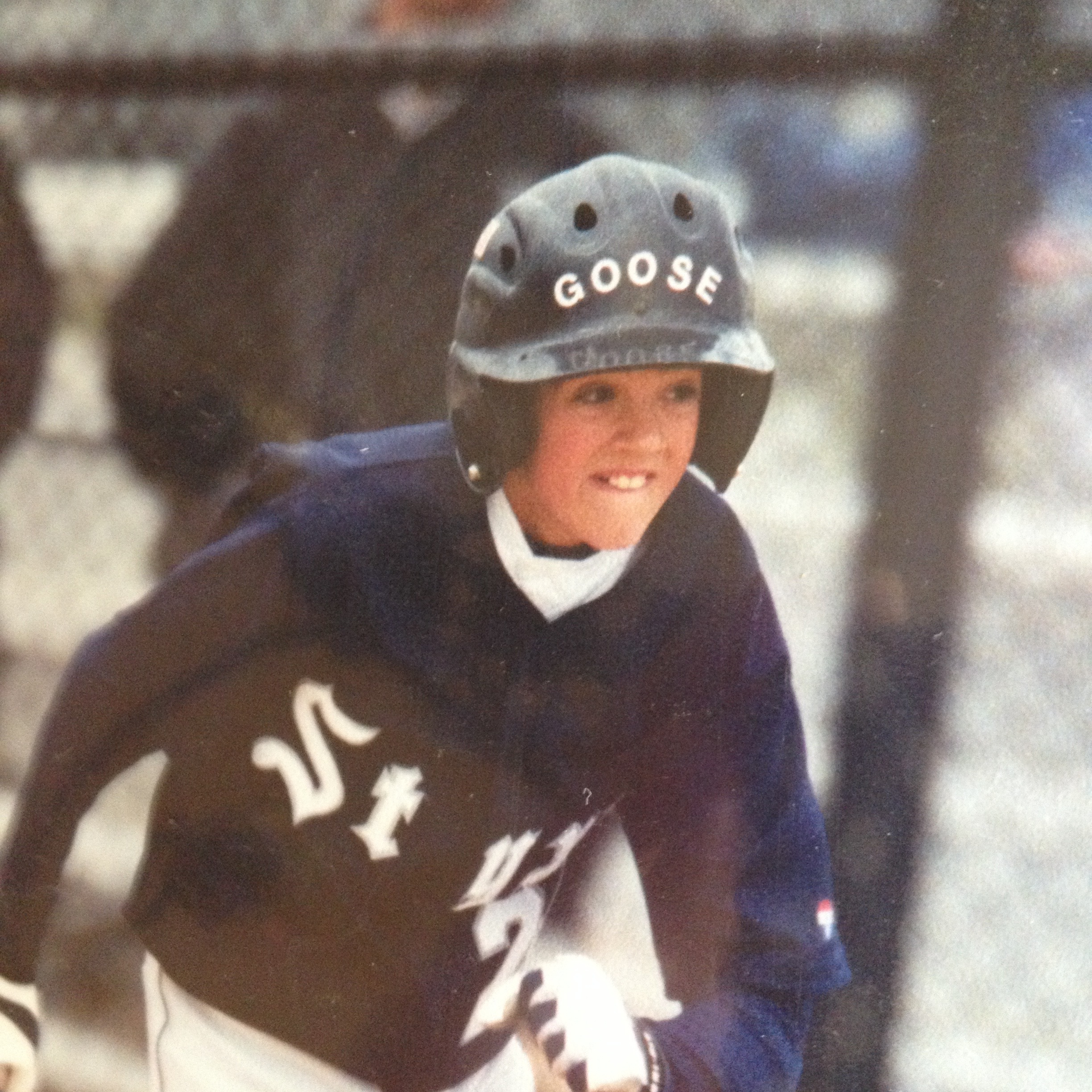

Kevin was a miniature ball of energy who remembers himself as the worst player on his 9-and-under team. Clair coached him and would pinch-hit little Kevin, who was quick and an excellent bunter, which was a big part of his role on the team.

That began to change as he hit 13 and 14 and shot up another foot. He had infused in himself the work ethic that comes with being a kid who feels undersized, and then was gifted that size, too. Often he made Clair stay outside until he could barely see the ball, long-tossing and building up arm strength as his father Fungo’d balls back to him, worried about his own arm.

Brian was tough on him, wanting the best for a little brother whose shot on the court he would block whenever he wouldn’t use his left hand. His father often was both his catcher and the least generous umpire Kevin has ever seen. The boyhood dreams were spelled out in the yard, on a rubber if not a mound: Game 7 of the World Series, ninth inning, bases loaded, no outs. Gausman delivered.

“He would catch me, and I would throw three strikes and he would call them balls,” Kevin remembered with both a smile and a friendly edge that has not quite fully softened a couple decades later. “He would be like, ‘What are you gonna do? How are you gonna react? Umpire might not be on your side. What do you do?’

“Some days I would lose it and go inside crying to my mom. ‘Mom, Dad is being mean, he won’t call a strike.’”

He wanted to be tougher. He wanted to be a righty Randy Johnson, whose power and demeanor and presence he idolized. He would bring the glove and his throwing hand inches in front of his face, eyes peering out toward the catcher in an impression of Johnson, and as his height grew so did his velocity. He needed more than a fastball, though.

And up

To be sure, though: The fastball was special.

In Kevin’s first game at Grandview, Adams, the varsity coach, grabbed at a radar gun and went to see the freshman game. Gausman’s first warmup pitch was 86 mph. Then 87. Then 88.

Gausman’s first three actual pitches in the game resulted in a strikeout.

“Oh boy,” said Adams, who’s now coaching with Rock Canyon in Colorado. “He’s going to be special.”

The more Adams got to know him, the more there was to like. He knew Brian and knew the family as good, loyal people. He saw Kevin’s athleticism, his easy-going nature and an arm that was rubber and, ironic in the Colorado chill, allergic to ice.

He would throw 100 pitches and then be on the field the next day long-tossing from 400 feet.

“It was like, what in the hell?” said Adams, who made Gausman ice his arm.

Gausman tried the ice and felt the next day as if his arm had stiffened up. Still to this day, he refuses, and the most prized arm on the best team in Major League Baseball goes for jogs for recovery instead.

“It didn’t matter if there was snow on the ground,” said Gausman, whose runs might stretch two hours. “If it was summertime, I had a hoodie on. If it was winter and there was snow, I’d have like three hoodies on.”

With that right arm, he did not need a second pitch to dominate high schoolers, but he would need another to get where he wanted to be — which was not necessarily Major League Baseball but the College World Series, which he attended every year with his family.

A lot had to go right for Gausman to develop into the superstar he has become: the desire, the makeup, the growth spurt, the power, being surrounded by talented kids like major leaguer Greg Bird, a high school teammate who caught him. And he had to come across Chris Baum.

Baum had pitched at New Mexico in the ’90s before bouncing around Independent leagues, his best pitch a type of splitter that he had picked up in college, when he saw someone from the Astros’ organization throw the disappearing, back-spinning pitch during a summer league in Arizona. Baum asked to see how it was thrown, got the answer, and 15 minutes later the player was gone, but Baum had a new weapon to work on.

And a lifetime later, a new pitch to show Gausman, who struggled for years to find a dependable second pitch.

“He just couldn’t get on top of the baseball well enough to throw a curveball or slider,” is the report from Brian, an endearingly critical brother and now a coach at Grandview. “To this day I’m like, how can you not throw a get-me-over slider every once in a while when you need to?”

With the Giants, Gausman has learned he doesn’t need much of a slider when he has the splitter. His hands are more commonly seen in basketball, globes with digits that can manipulate what Gausman sometimes calls a “fosh” — a cross between a splitter and a changeup. Gausman also can tweak the grip to turn it into a circle change that moves a bit less and hangs in the strike zone. Hitters think it’s a poor splitter; the next actual splitter they see vanishes out of the zone.

“We tried to show him three or four different versions of changeups, and then I showed him the one that worked for me,” said Baum, who was a JV coach then and is now a math teacher at the school. “He started playing with it, and it just worked — it worked for him the way it worked for me.

“You didn’t have to change your motion. You throw it as hard as you can every time like you’re trying to throw a fastball by somebody, and it just dies. The spin rate gets cut dramatically, but it still reads as a fastball because it’s spinning backwards, and it just disappears when it gets to the plate, just falls off the table.”

There is some debate about which year Baum taught it to Gausman, both time and tweaks of grips in those seasons obscuring a few particulars.

But Gausman still remembers his initial reaction when Baum was demonstrating — it’s similar to the reaction of hitters who have to face it today.

“I remember being like, what the hell is this?” Gausman said. “He was like, ‘It’s not a split, but it’s not a change.’

“I started throwing it. It was pretty terrible for a year at least.”

Brian says there are still nicks on his legs from trying to catch it. Clair wanted to wear shin guards.

“It’s kind of like giving a kid the keys to a Ferrari and then hoping he can keep it on the road,” Baum said.

The pitch moved, and so did Gausman as he was drafted in the sixth round in 2010 by the Dodgers.

Keep rising

He had seen, though, what stripped-down professional baseball looks like, having journeyed to Burlington, N.C., to see Brian pitch and realizing he was among the few spectators there. He also was moving into LSU when the Dodgers — who were committing major money to another LSU commit in Zach Lee — came at him with a lesser offer.

“You’re going to make my mom move my stuff in and then make me leave [LSU], it better be a good offer,” Gausman said through a laugh.

He was a star from the onset, but grew into a 2012 First-Team All-American under the guidance of that season’s pitching coach, Alan Dunn, whose discipline Gausman credits heavily for his success. In the one year, “I gained five, six years of knowledge,” Gausman said.

It was the little things — the focus on remaining consistent with everything, on becoming fully a baseball player for a kid who really only played baseball games during baseball season growing up. They sat talking about pitching after practice. Dunn had come from the big leagues, and he wanted Gausman to get there, too.

To be clear, Dunn came from the Orioles, with whom he had been the minor league pitching coordinator. Buck Showalter, then the Orioles manager, kept buzzing Dunn about Gausman, who became the No. 4 pick in 2012.

And back down

The more people you talk with, the more answers you get about why Gausman never became the full-fledged ace Baltimore had banked on. Gausman appeared in 21 games in the minors before debuting in 2013. His ERA was 8.84 after four starts; soon was demoted; soon was a reliever; soon was building back up in the minors.

“I think he needed to be in Double-A pitching every fifth day for a couple years just to learn that process,” Clair said. “But the Orioles said they want to win, so they kind of moved him up and down.

“I remember him driving one time back to [Triple-A] Norfolk, and he said, ‘I’m not sure I have a place to stay when I get there.’”

The other contributing factor entailed 2013 being a prehistoric era compared with today’s pitching technology. There were preparation and data issues for a pitcher who continually tried to use his slider and tinkered with a curveball, while throwing his best pitch, the splitter, about 20 percent of the time. It wasn’t until Atlanta, to whom he was dealt at the 2018 trade deadline, that he realized he should be throwing his best pitch more often and stop getting beaten on his third and fourth best offerings.

Still, sustained success was out of reach. He finished well in 2018 with Atlanta then pitched to a 6.19 ERA in 16 games before one of the best pitchers on earth was designated for assignment. There was pain, but there was not a loss of confidence or control. He caught on with Cincinnati, which had respected pitching mind Derek Johnson from Vanderbilt.

“He’s a listener. He’s always been that way,” Clair said. “He picks up a lot from coaches. I think he likes to hear that — he wants to know, ‘Hey, you’re dropping your shoulder a little bit too much here.’ ‘You’re trying to overthrow,’ some of those things. I think he needs that more than some guys that are veterans that have been around as long as he has.”

With the Reds, the biggest pick-up was picking up his catcher. Upon coming over midseason, Johnson noticed he was looking toward third base too long and not craning his neck enough toward the mitt quickly enough.

Flaming out of Atlanta’s rotation had cost him a shot at a starting job with the Reds, but he showed dominant stuff in relief.

“Johnson was like, ‘The best free throw shooters in the NBA stare at the rim the longest,” Gausman said.

But the Reds did not believe in him enough to tender him a contract that might have been worth $10 million in arbitration. One of the best pitchers on earth was a free agent who just wanted a starting opportunity.

“I think it was really hurtful,” Clair said, though it did not lead to outward anger.

“I always had confidence in myself, even at the lowest point in my career,” Gausman said. “I always felt like I was just having bad luck.”

The Giants’ luck turned. An organization that was beginning to make a name for itself by picking up high-upside talent that had not been maximized elsewhere pounced, and $9 million later Gausman was the newest project of Andrew Bailey, Brian Bannister & Co.

“Just knowing this was a guy that who had top-five pick pedigree,” Farhan Zaidi said. “Really good person — whether it was Baltimore, Atlanta, Cincinnati, really good teammate was what everybody we talked to about him said. It was just a guy that clearly had high upside and maybe was just an adjustment or two away from getting back to being a really good starting pitcher in the big leagues.”

The peak

Gausman thanks an organization that has advised him to throw his splitter more — and more, and more. 28.5 percent of the time during last season’s breakout; 38 percent during a first half of 2021 that is bringing him back to Coors Field for a first All-Star Game, which he will not participate in because he pitched Sunday but still will attend with family.

His 1.73 ERA only looks enviously at deGrom’s; a slider he could not master is mostly shelved; those curveball experiments are over.

In at-bats that end with splitters, opposing hitters are 20-for-184 (.109). According to Statcast’s Run Value tally, only a four-seamer from the White Sox’s Carlos Rodon has been a better pitch this season. More than half the time an opposing batter swings at Gausman’s splitter, he misses.

“It’s been a bumpy ride, it hasn’t been smooth,” Gausman said. “I’ll take all those calluses, and I kind of deserve everything. I feel like I’ve put in the work, and you can’t say that I didn’t work for it.”

He will arrive as a superstar he had never been before, and yet he will arrive as a Kevin Gausman everyone around him says has not changed. There will be family time, there will be smiles that come easily, there might be a battle under the boards with Brian, in which the competitor in Kevin arises.

But there won’t be an outburst, even as his roller-coaster sails into the clouds.