On November 19, 2000, Bobby Thomson brought Joshua Prager to church.

By then, Prager knew all about the secret that had been eating away at Thomson’s insides for five decades. Thomson’s former New York Giants teammates had already told Prager about electrician Abraham Chadwick’s buzzer system, the Wollensak telescope used from a window in the Polo Grounds center field, and backup catcher Sal Yvars’ role in the 1951 Giants’ elaborate sign-stealing scheme.

It was finally time for the architect of the most dramatic home run in baseball history to spill.

That day in Watchung, New Jersey, Thomson and Prager held hands, sang “We Gather Together” and read scripture. Then, after 50 years sworn to secrecy, Thomson recalled how the Giants turned their season around when they started stealing signs. It was a relief for Thomson; he could finally take honest credit after years of dancing around the subject and shrugging off praise.

So did Thomson steal the sign on Ralph Branca’s ninth-inning, 1-0 fastball? “I’d have to say no more than yes,” he told Prager.

Baseball was once a religion in America. Still is for some. To question faith is to pursue the truth. Here, Thomson found peace with it. And Prager had the final piece he needed for his story.

Two months later, on the front page of the Wall Street Journal, a headline read: “Was the ’51 Giants Comeback a Miracle, Or Did They Simply Steal the Pennant?”. Journalists had produced countless amounts of literature dedicated to Thomson’s famous home run, but before Prager’s reporting there were only whispered rumors of sign-stealing — unfounded allegations not nearly strong enough to taint the “Shot Heard Round The World.”

As a reporter, Prager’s ability to painstakingly uncover details and present them dramatically forced fans to reconsider the “Shot Heard Round the World.” But it’s his personal experience that makes Prager uniquely capable of showing how Branca and Thomson’s lives changed after Oct. 3, 1951.

“The Echoing Green,” Prager’s definitive book that expanded on his sign-stealing reporting, is as much a story of a famous crack of the bat and a cultural touchpoint in American history as it is about the human condition. It’s about secrets, grudges, and what happens to a hero and a goat whose lives diverged at one nexus moment.

“I think if there’s one thing that marks me above all as a writer, it’s empathy,” Prager told KNBR. “I try very much to empathize with the people I write about, present things from their point of view, and understand them.”

It took Prager almost six years to conduct 2,000 interviews with 500 people and write the 546-page book. He typed every letter of every word with his right index finger.

There was no way anyone could’ve seen the blue truck coming on May 16, 1990.

Prager, then 19, was traveling in Israel, sitting in the back left side of a minibus when the truck slammed into him. The accident killed one person and broke Prager’s neck.

At first, Prager was a quadripeligic, paralyzed from the neck down. It took him months to learn how to breathe on his own, sit, stand and walk. A hemiplegic, his body was divided vertically, with more paralysis on his left side than right.

Before the accident, Prager could palm a basketball. He always loved playing baseball, but wanted to become a doctor because he knew he’d never make it to the big leagues.

After the accident, Prager started at Columbia University in a wheelchair, where he realized the university wasn’t accessible. There were hardly any wheelchair ramps or working elevators, which prevented him from attending classes.

For one class particularly interesting to Prager, the professor suggested he ask football players to carry him up the stairs. That was it. Prager had written letters urging the school’s administration to fix the elevators, but his pleas went ignored for months. So instead, he wrote an article in the school newspaper explaining the situation, urging the university to right its wrongs.

George H.W. Bush had recently passed the Americans with Disabilities Act, and Prager invoked it in his column. Within days, the school held a press conference and took action.

“It made me realize the power of the press,” Prager said.

He graduated in 3.5 years, all in a wheelchair, discovering a new career path in the process.

There’s something about secrets that Prager has often gravitated to in his reporting. He quoted “Libra,” the Don Delillo novel about John F. Kennedy assassination theories.

“There’s always more to it,” Prager cites. “This is what history consists of. It is the sum total of the things they aren’t telling us.”

But Prager isn’t conspiratorial. He’s curious. His uncovering of secrets tells real history — the throughlines of truth that, once revealed, turn untold history into fact.

His most recent book, “The Family Roe,” about the landmark Roe v. Wade case, came out in early September. A revelation from that reporting was the relationship between Norma McCorvey — the anonymous plaintiff in the landmark case — and the daughter she couldn’t abort, Shelley. One of Prager’s next projects, too, is related to a World War II-era secret.

For “The Echoing Green,” the secret at hand put into question what many consider the most dramatic home run ever. In mid-August of the 1951 season, the Giants trailed the Brooklyn Dodgers by 13.5 games. Then NY won 16 straight games, one of the longest winning streaks ever, which included 13 home games with their sign-stealing scheme intact.

Abraham Chadwick, a Dodgers fan working for the Giants as the Polo Grounds’ electrician, installed a bell-and-buzzer system that went from the center field clubhouse that connected to phones in the dugout and fair-territory bullpen. Third base coach Herman Franks would perch in the clubhouse, peek through a hole in the wall with a Wollensak telescope to decode the catcher’s sign. The buzzer — one for fastball, two for offspeed — alerted backup catcher Sal Yvars in the bullpen, and he’d relay the sign to the batter with body language signals.

In 53 days, with the system in place, the Giants made up the gap in the standings to finish the regular season tied with Brooklyn, 96-58.

Thomson’s go-ahead home run in the ninth inning of the final game of the playoff — the first nationally televised series in American history — sent the Giants to the World Series.

Prager first heard about rumors of sign-stealing while talking to his friend Barry Halper, a memorabilia collector, in 2000. Despite rumors, the secret persisted through five decades. But after talking with Halper, Prager tracked down each living member of the 1951 Giants — including then-rookie Willie Mays — plus the last living coach, to unearth the truth.

When shortstop Alvin Dark said “I know nothing, I know nothing, I know nothing,” Prager realized there was something going on. After gathering all the details, Prager called Thomson. In one breath, he asked him what it was like to carry the secret for all those years. Thomson invited him to church.

Thy hour and thy harpoon are at hand! -Herman Melville, “Moby-Dick,” 1851.

Prager leads every chapter of “The Echoing Green” with a quote from famous literature, Melville to Shakespeare. Most of them just came to mind as a theme related to the upcoming chapter’s story. But for the building climax of the Giants-Dodgers playoff series, nothing immediately stuck out.

Then, a showdown between man and beast — at long last. Thy hour and thy harpoon are at hand. Prager thought of “Moby Dick” when brainstorming examples of epic confrontations. He hadn’t read the classic before, but tore through it cover to cover in search of a passage that spoke to the Thomson-Branca dynamic. It’s by far Prager’s favorite book.

In writing about Thomson and Branca, Prager was also writing about himself — though he didn’t realize it at the time.

“I realized I loved writing about how life changes in moments,” Prager said. “Kind of a before and after of when one moment changed their lives. It happened in the “Goodnight Moon” story, it happened in the baseball story, and of course it happened in my life.”

Thomson was never able to take full glory for the home run and an ankle injury prevented him from reaching his full potential before a life of selling insurance and paper after baseball. He eventually eschewed the game he loved. Branca suppressed his anger about the pitch and lived happily with his wife, despite a lack of MLB opportunity later in his career. Their up-and-down relationship extended decades, with an unspoken secret hanging over them through countless public appearances and autograph events.

Meanwhile Prager, after finding the man who broke his neck in search of closure, learned everyone is a product of both genes and experience. And writing the book allowed him to shake off somewhat of an imposter’s syndrome, as he saw himself become an author like so many he admires.

“Writing about them helped me deal with my own loss,” Prager said.

Prager’s reporting also helped Branca and Thomson grapple with the truth behind the home run. Thomson, though he denied glancing up into the bullpen for a sign on Branca’s pitch, admitted the scheme helped the team. Branca had heard rumors through the years, but never wanted to appear like he was making excuses. They recognize their stories are incomplete without the other’s.

“We’ve been together enough,” Thomson told Prager. “We need each other.”

Prager needed them, too, both professionally and personally. Prager attended Thomson’s funeral and did the eulogy for Sal Yvars. He did book signing events with Branca.

The reporting process took him from Ralph Branca’s home in Westchester, New York to Thomson’s native Scotland. Yvars slammed a door in Prager’s face, but eventually told him everything. The family of Henry Schenz, one of the original clubhouse spies, showed Prager the telescope he and the Giants used in Westford, Massachusetts. Franks refused to talk for years, then 19 days before dying revealed he saw Thomson look up for the sign right before hitting the home run that won the Giants the pennant.

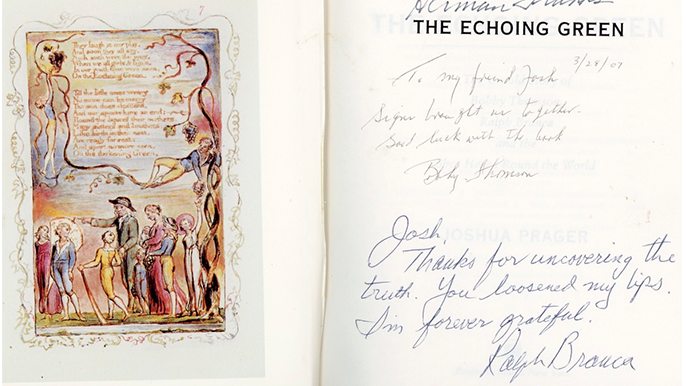

“Signs brought us together,” Thomson inscribed inside the cover of Prager’s copy of “The Echoing Green.”

“You loosened my lips,” Branca wrote right underneath.

No one will ever know exactly how much the sign-stealing helped the 1951 Giants. Even when knowing what pitches are coming, batters still have to put barrel to ball. But some lifelong Giants fans still have trouble grappling with the sign-stealing.

Harvey Weinberg, a 76-year-old member of the New York Giants Preservation Society which Prager speaks with occasionally, believes there’s “circumstantial evidence” Thomson didn’t take the sign. One New York-area elementary school teacher wrote a play based off “The Echoing Green” for his students to perform. Many other fans, especially Bay Area natives, are unaware of the sign-stealing scheme.

“Not everything has to be a storybook fantasy,” Prager said. “Life is more complicated than that. And it’s still a great moment.”

Steven Rothschild, another NYGPS member, looks back on the homer with a clearer understanding because of Prager’s “on the verge of brilliance” reporting, but still great appreciation.

“Whether he knew the sign or not, the comeback was amazing,” Rothschild said.

Prager now lives with his wife and two daughters in New Jersey. In his home office, Prager types 30 words per minute. Around him are seats from the original Polo Grounds, which he sometimes sits in. Above on the wall hangs a painting of Thomson’s legendary home run, signed by Thomson and Branca.