Rodney Fort, a sports economics professor at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor who’s written seven books about sports business, has followed baseball labor relations since he was a high schooler in 1981.

KNBR.com spoke with Fort to learn more about the current state of the MLB Lockout from an economics perspective. Fort said the two sides aren’t too far apart — “this is nothing like 94-95,” he said — but added he believes the focus of the MLB Players Association may be somewhat misguided.

The MLBPA and owners have been negotiating mainly over “core economics.” For the players, that has meant trying to get young players paid earlier through arbitration or hitting free agency quicker. But Fort thinks they should take more of a macro view.

“I think players and their agents are slow on the uptake of figuring out how much more baseball players are really worth than, say, their WAR value or something like that,” Fort said.

“It’s not that that value isn’t important. It’s just that if you think about being a $14 million per year baseball player because of the way you play baseball, you’re forgetting about the other two or three million you might be contributing to revenue because of how the fans feel about you. Or because the games are being played and owners are making money off parallel endeavors like gambling in the stadium or gambling in general.”

Fort said that dynamic — all the extra ways players generate revenue — may be going overlooked in the negotiations.

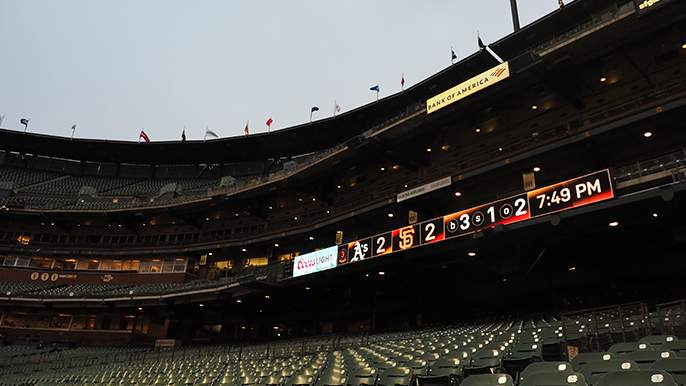

Fans buy tickets to see Shohei Ohtani when the Angels are in town, something that doesn’t factor into his OPS+. There’s a buzz around town when the Giants signal they’re going all-in by trading prospects for Kris Bryant at the deadline; energy that converts to revenue.

But Fort argues there are also more tangible ways players generate revenue for their clubs — and the league — that they’re not currently negotiating for. The biggest missed opportunity could be money from gambling.

“Everybody still remains focused on what really is an outdated way of thinking about how baseball players get paid, which is according to their contribution to winning on the field,” Fort said.

Sports gambling is already pervasive around baseball. Draftkings and MGM Resorts are both official sponsors of MLB. Whenever sports gambling is legalized more widely, it’s likely most ballparks add on-site sportsbooks. During games, broadcasters promote props like if a player will hit a home run or not.

But in the current CBA, none of that revenue goes to the players; the union would need to bargain to be included. An American Gaming study from 2018 projected MLB stands to gain over $1 billion from gambling revenue annually.

“The value of that gambling doesn’t happen unless games are played, and games don’t get played unless players play them. Nobody comes to watch owners own,” Fort said.

What the MLBPA appears to currently be vying for — arbitration reform, higher CBT, earlier free agency — would still only help select players, Fort said. The vast majority of the 1,200-member players association aren’t productive enough to ever earn a big payday in free agency or even in arbitration. But sharing revenue from something like gambling equally throughout the union could benefit players wholesale.

In recent years, player salaries haven’t kept pace with overall league revenues, something Fort credits to owners taking advantage of the competitive balance tax and revenue sharing. For the latter, Fort said smaller market teams who benefit from league revenue sharing often don’t spend that money on-field product, instead pocketing it and thus hurting the market.

But the fact league revenue has outpaced player earnings is the basis of the “core economics” at play, and Fort said changing when players earn bigger salaries likely won’t fix the fundamental issues. Neither would raising the competitive balance tax without fixing it to overall league revenue or increasing revenue sharing between big and small market teams, he added.

Based on public posturing from the owners, it’s possible management won’t budge on revenue sharing in any sense. But Fort said building other revenue streams into the CBA negotiation process should be the players’ biggest priority.

“It’s probably time for the player side to wake up and realize that they’re contributing individually millions more than just what their play is worth,” Fort said.

“Players need to start recognizing that past agreements in the collective bargaining agreement are dampening pay. And there’s a whole lot of revenue streams that they’re not really capturing well. So as revenues go up, if you’re dampered and not capturing, your percentage is not going to keep very good pace. The amounts will still be larger, owners will always point that out. But if baseball revenues are growing by 7% and salaries grow by 3%, somebody’s keeping the rest of the money. And so the trick is to figure out how much of that difference is generated by players and to be more aggressive about moving it away from owners and toward players.”