For the first nine years of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, there were no official guidelines for voters to give players the sport’s greatest honor.

Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Babe Ruth and Honus Wagner made up the first Hall of Fame class in 1936. Then in 1945, the Hall of Fame Committee formally adopted rules for eligible candidates that the Baseball Writers Association of America could consider.

Hall of Famers, the committee decided, “shall be chosen on the basis of playing ability, sportsmanship, character, their contribution to the teams on which they played and to baseball in general.”

Over the years, those words — now commonly known as the character clause — have become a tool for voters to keep players out of Cooperstown. And the 2022 class is “the most character clause-y ever,” Ryan Thibodaux, who’s been tracking Hall of Fame ballots independently since 2013, told KNBR. On the 2022 ballot there are suspected PED users, convicted PED users, domestic violence accussees, and a conspiracy enthusiast bigot.

For decades, BBWAA voters have had the impossible task of parsing through players’ resumes, behaviors, values and statistics. It’s entirely subjective; any voter can put more stock into a player’s WAR or one’s nobility. That’s the system baseball’s chosen, with all its benefits and warts.

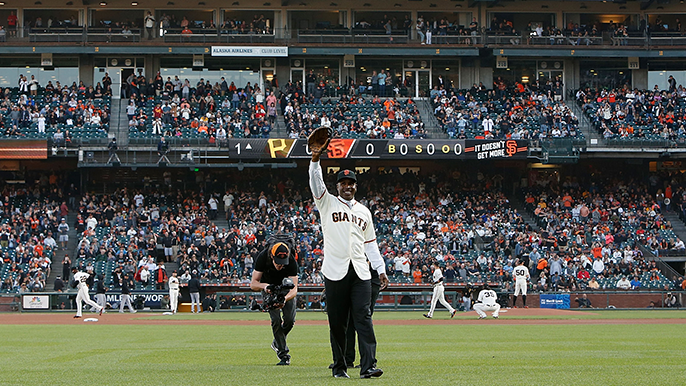

For San Francisco Giants legend Barry Bonds, the pendulum has swung too far away from his unparalleled resume for his Cooperstown chances. The all-time home run leader won’t be enshrined by BBWAA writers in his final year on the ballot; one recent projection model gives him a 0% chance at reaching the necessary 75% of ballots.

The 2022 Hall of Fame class will be announced on Jan. 25. The only thing keeping Bonds out of it: his character.

Judge Landis, the first commissioner of baseball, served from 1920 until his death in 1944. Landis oversaw the fallout of the 1919 “Black Sox Scandal” and imposed crackdowns on illegal gambling. He also failed to integrate the sport, reigning over an era before Jackie Robinson broke the color line.

Arguably the most lasting action Landis made as commissioner was introducing the character clause — something no other American Hall of Fame considers.

But the motivations behind the clause at the time were much different than how its application has evolved since. Jay Jaffe, senior writer at Fangraphs and author of “The Cooperstown Casebook,” said Landis was searching for a “backdoor way” to get Eddie Grant, a third baseman who was killed in World War I, into Cooperstown.

Grant wasn’t enshrined. But for decades, Jaffe said the character clause was used to make the Hall of Fame case for, not against players.

“Prior to the arrival of Mark McGwire on the ballot in 2007, you rarely saw mention of the character clause except when it was in the context of justifying a vote in favor of a candidate,” Jaffe told KNBR.

While voters rarely cited the character clause, they enshrined a reported Ku Klux Klan member in Rogers Hornsby, a self-admitted cheater in Whitey Ford and countless other nefarious characters. Voters overlooked their “sportsmanship” and “character” in favor of their contributions to their teams.

But as baseball changed with the influx of performance-enhancing drugs, and society changed around it, voter perception naturally evolved, too.

Álex Rodríguez and Manny Ramirez, two of the greatest right-handed hitters of all time, were both suspended for PEDs during their careers and face a steep mountain to climb toward Cooperstown. Omar Vizquel, accused of domestic violence and sexual harrassment of a batboy with autism, is tanking away from Cooperstown like the 2008 financial crisis. Curt Schilling, who tweeted his support for Jan. 6 Capitol rioters, posted a meme supporting lynching journalists, and compared Muslims to Nazis among other hateful incidents, asked to be removed from the ballot when his candidacy fell short last year.

“I think what we’re seeing with the growing influence of the character clause citations is the people, we’re talking about domestic violence within sports a lot more,” Jaffe said. “It shows we care more about these matters. And it shows our choice for who to honor with this highest of baseball honors is more than just a rubber stamping of the stats.”

Then there’s Bonds, who has denied using steroids and was never officially reprimanded by MLB for cheating. He was indicted in 2007 on charges of perjury obstruction of justice for allegedly lying to a grand jury during the federal government’s investigation of BALCO. Leaked testimony revealed he admitted to unknowingly using “the cream” and “the clear.”

Two 2006 books — “Game of Shadows” and “Love Me, Hate Me” — in addition to reporting in several outlets, detailed Bonds’ alleged steroid use. Gary Sheffield told Sports Illustrated Bonds introduced him to BALCO, and one of Bonds’ ex-girlfriends testified that he admitted an elbow injury was caused by his steroid use.

While Bonds’ links to performance-enhancing drugs are well-documented, they’re not the only thing that could impact his integrity. He was also accused of domestic violence twice, though Thibodaux said he hasn’t seen a voter leave Bonds off their ballot because of that specifically.

PEDs are the main issue. Before Bonds was understood to start using, from 1986 to 1996, he amassed 334 home runs and 380 stolen bases — numbers no other player has ever recorded in their careers.

Bonds’ 762 total home runs may never be topped. He won seven Most Valuable Player awards; no one else has more than three. He holds single-season records for home runs (73), on-base percentage, slugging percentage and walks. No hitter has ever been more feared.

But voters weigh those milestones versus the PED accusations that put them all into question differently. And the most famous, most all-encapsulating Bonds relic is already in Cooperstown: his record-breaking 756th home run ball, complete with an asterisk lasered into it.

Bonds and Roger Clemens — a similarly dominant force with a similarly questionable character résumé — are the only players clearly linked to steroids to receive at least 50% of votes.

That doesn’t include rumored PED users, like Mike Piazza and Jeff Bagwell, who are already in the Hall. Ramirez and Rodriguez, the suspended cheaters, are polling around 40%.

“There’s no consensus on how to handle these guys,” Jaffe said. “Everything ranges from zero tolerance to complete indifference.”

Bonds and Clemens are in their own class. They’re each in their final year of BBWAA voting, after which they could potentially get nominated and elected by an era committee.

But traditional, BBWAA voting appears to be a dead end for Bonds.

In 2013, his first year of eligibility, Bonds appeared on 36.2% of ballots. He hovered around there until 2017, the same year Bud Selig was inducted, when he cracked 50%.

If Selig — who as commissioner oversaw the era with the most rampant cheating and failed to take control of the game — of all people could get in, surely Bonds belonged.

But Bonds’ popularity has plateaued. He fell 53 votes shy of the 75% threshold in 2021 and is destined for a third-straight year in the low-60s.

Thibodaux said the only way Bonds could get elected in his final year is if a large cohort of voters who have always left him off their ballots include him as somewhat of a statement. But there’s no evidence of this one day before the official announcement.

Trends have emerged with Bonds (and Clemens) supporters, according to Thibodaux. Voters who tend to reveal their ballots publicly are more likely to check Bonds. So are younger voters, who are more apathetic to character clause arguments.

Local writers who saw Bonds up close on a daily basis are more supportive; seven of eight San Francisco Chronicle reporters with a vote vouched for the slugger.

Janie McCauley, an Associated Press reporter based in the Bay Area, covered Bonds for five seasons. McCauley, who was featured in ESPN’s recent special on Bonds’ career and Hall of Fame chances, has voted for Bonds every year since she got her first ballot in 2015.

“I don’t feel that I’m the moral compass for the Hall of Fame,” McCauley said. “I take (the character clause) into consideration, but I also try to see the big picture of baseball.”

McCauley dropped Schilling from her ballot, but added Ramirez, Rodríguez and David Ortiz. Andruw Jones, who was arrested for a domestic battery incident in 2012, also makes McCauley’s ballot.

The last 25 years of baseball has been defined by contradictions and inconsistencies. Most ballots reflect that because of the choices voters face. Those choices begin with how one views the character clause.

Some say the Hall of Fame isn’t the Hall of Fame without Barry Bonds. Others say a cheater and alleged domestic abuser shouldn’t be celebrated by a sport that at least claims to hold higher values. The question comes down to whether the Hall of Fame is a monument to honor the greatest or a museum to chronicle the sport’s history. Depending on a voter’s interpretation of it, the character clause either puts that dichotomy into focus or completely blurs it.

For the 10th straight year, though, enough voters are clear enough on the question to keep Bonds out.