All that the 49ers are and all they strive to be offensively is exemplified by their talisman, George Kittle. And since San Francisco stole him in the fifth round of the first Shanahan-Lynch draft class back in 2017, he has been the do-it-all gladiator who barrels ahead with a full head of steam in every aspect of his game.

At his best — and Kittle is arguably the best player at his position when healthy — he’s an omnipresent force.

But over the past three seasons, Kittle has been injured more frequently. He and the 49ers, of course, dispute that this is because of his fight-through-contact style and heavy workload.

Kittle, at a level unlike any other tight end in the NFL, is asked to block in the run game, work one-on-one in pass protection (an uber rare ability) and make run-after-catch plays and contested catches with regularity. He even takes some carries in ways most tight ends don’t.

All the things that make Kittle special are also why he’s suddenly become an issue. Since signing a record-breaking, five-year, $75 million contract before the 2020 season, Kittle has played 12 of a possible 23 games.

This is not for a lack of preventative care on his part. Kittle prepares his body as much as any player, working with strength trainer Josh Cuthbert and a host of other players in the offseason, and has one of the more extensive pregame routines among his teammates.

In spite of that, injuries, which have included knee sprains in both 2019 and 2020, a foot fracture in 2020, and now a calf strain this year, have cost him valuable games.

He has also had a torn labrum in his shoulder since 2018 which he’s declined to address surgically, saying that it would interfere with valuable offseason lifting time.

Kittle argued — and pretty staunchly, at that — on Thursday that these are freak injuries, when asked if there might be ways for him to better protect himself.

“Oh, well, let’s see. Two of my injuries were taking a helmet to the kneecap and I had a broken foot and I had a lower body injury this time and not a single one of those things was from being overly physical or attacking people or truck sticking people or the run game, so I don’t really know how to answer that,” Kittle said. “I’m just gonna try to keep being me.”

“I mean, I feel like I do a lot of stuff in the offseason, in season. All I care about is football and make myself available and sometimes you know, football is a violent game and it’s very unforgiving. Stuff happens and you just got to kind of deal with it.”

Whether the injuries are all “freak” in nature is besides the point. Kittle has been hurt over the last three seasons. He is as physical a player that there is, and has reminisced in the past over tight end coach Jon Embree encouraging him to run through people.

That’s probably not a sustainable model, especially given what the 49ers ask of him. In his four games this season, Kittle leads all tight ends with an average of 65.5 snaps per game and blocks on 50.8 percent of those. Keep in mind that he continued that workload while dealing with his calf injury, playing him for 70 snaps in the loss to Seattle before he was placed on injured reserve.

Kyle Shanahan’s response to any suggestion that Kittle’s snaps should be decreased, or his load lessened, was dismissal.

“I think when you talk about workload for tight ends, it’s about training camp, it’s about practice, it’s about stuff like that,” Shanahan said. “When a guy’s not healthy, you’ve always got to do that. But I haven’t heard of people managing a tight end, especially one like Kittle.”

“Tight ends go. They play every play usually. Lots of them, you have different personnel groupings, but most tight ends are over 80-percent of the game. But Kittle is always going to play through stuff and go out there when he isn’t a hundred percent. And when he’s not a hundred percent, that’s when you’ve definitely got to do that. But I’ve never done that with a tight end before though.”

The difference is that Kittle’s snap counts come at a prolific, league-leading level, while being asked to block at an extremely high level, too.

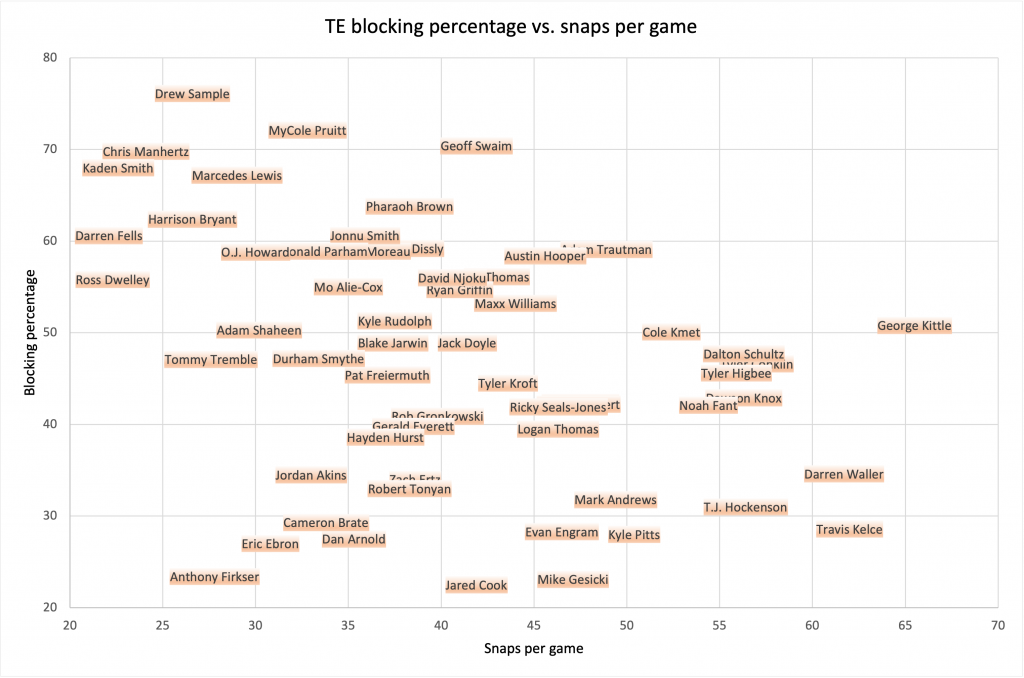

To illustrate what Kittle’s snap and blocking numbers mean in the context of league-wide tight end usage, here’s a chart of the top 60 tight ends in the NFL this season based on snap count, and their blocking rates.

It’s a little cluttered, but Kittle is clearly on an island. When you look at the other elite tight ends in the league, in Darren Waller (34.6 percent), Mark Andrews (31.8 percent), Travis Kelce (28.6 percent) and Kyle Pitts (28 percent), they all block roughly 15-to-23 percent less often than Kittle does.

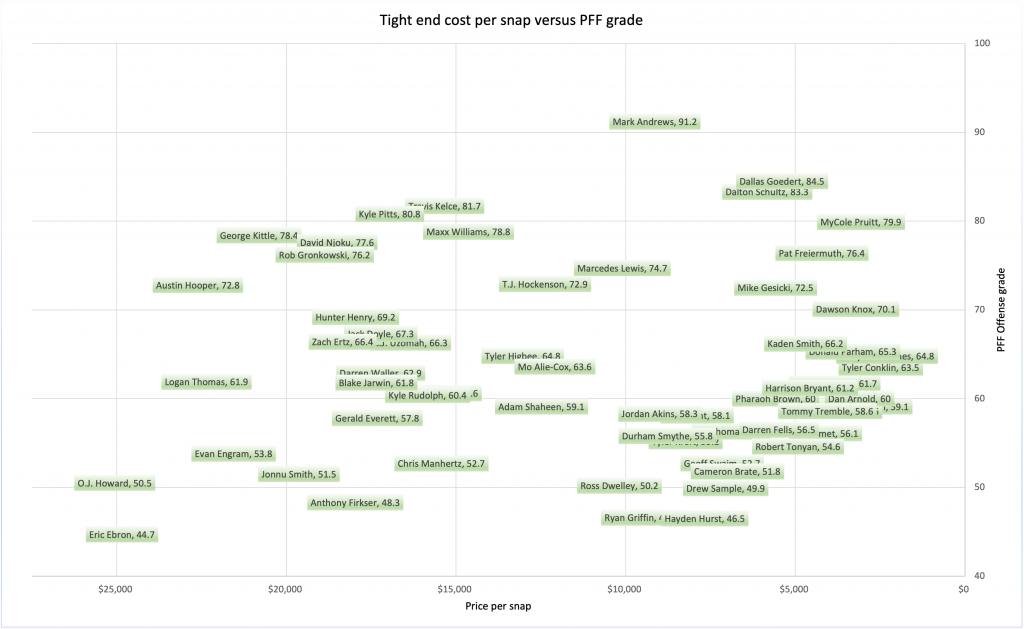

And when you look at Kittle’s blocking numbers in the context of his cap hit, he’s even more of an outlier.

The average annual salary of a player who blocks more than 50 percent of the time (among the top 60 most-snapped tight ends) is $2.78 million. Kittle’s yearly average is $15 million.

The average 2021 salary among those 50-percent-plus blockers is $2.62 million. Kittle’s 2021 hit is $5.45 million.

Sometimes those numbers can fail to reflect how much money players are actually due, when taking guarantees into account. The average total guaranteed money for a player who blocks more than 50 percent of the time is $4.06 million. Kittle has $40 million guaranteed.

The average blocking percentage for tight ends who take more than 45 snaps per game is 40.29 percent. Again, Kittle is averaging 65.5 snaps per game and has the highest blocking percentage (50.8 percent) among tight ends who average 50-plus snaps per game.

This is not to say the 49ers need to shelve Kittle or that Kittle shouldn’t block.

He’s far too valuable and impactful for that, and some of his more dangerous plays have come on screens. But Shanahan and Mike McDaniel indicated that if Kittle is healthy, they will not make an attempt to lighten his load.

McDaniel said it’s difficult to take Kittle off the field in any aspect.

“As far a healthy player, trying to protect him from himself, that’d be a tough, almost impossible task because you’d be picking arbitrary plays and saying, ‘Hey, okay, yeah, we’re not going to use you here because you might get hurt.’ I mean, that’s every play for a player,” McDaniel said.

“So we make sure, it’s a testament to George Kittle and how in shape he is really that we’re able to use him. But it’s kind of a hard thing to kind of say, ‘Hey, this really good player, that’s really good with the ball in his hands that our team depends on, we’re not going to give him the ball.’ Now, if defenses say, ‘hey, we’re not going to let you throw to him.’ That’s a different story. And that happens from game to game.

“But in terms of using him, when a guy is healthy, it’s football, so you play your players. He plays a physical type game and he will continue to learn how to keep himself out of harm’s way as best he can. But, it’s like an offensive lineman. Should we tell Trent to take half the game off? So, it’s a tough deal. We’ve never really approached it that way and I don’t really see players being substituted for reasons other than you might not be good on this play or you’re tired and you can’t perform at the best of your ability.”

When San Francisco cut MyCole Pruitt this offseason, they ridded themselves of a valuable blocking tight end who has been one of the most all-around productive tight ends in the NFL this season. He’s blocking 72.1 percent of the time (and crucially, 72.5 percent of the time in-line) and his 79.9 PFF grade ranks eighth-best among tight ends. Having a deeper tight end room with him around, could have eased some of the burden on Kittle.

The chart below shows a player’s price per snap (2021 cap hit divided by snaps) and their PFF grade. It’s an inexact measurement that should be taken with a grain of salt, but it shows, essentially, who has been the most productive for the cheapest cost. Pruitt is one of the clear leaders in that regard.

This isn’t about giving Kittle a pitch count or taking him off the field, as McDaniel put it, for “arbitrary” plays.

It’s about being more proactive about lessening his load, involving Charlie Woerner more frequently, and ensuring that the five-year, $75 million contract Kittle signed doesn’t suddenly become an albatross investment.

The point of all this is that Kittle is on the field more than any other tight end, and the tight ends who are anywhere near him in snaps either take far fewer blocking snaps than him and/or aren’t paid anywhere near what he’s paid.

The Rams’ Tyler Higbee is the closest comparison, who makes roughly ($5.83 million) what Kittle is making this year ($5.45 million) and roughly half ($7.25 million) of what Kittle makes year over year ($15 million), but he is still taking about 10 fewer snaps per game and blocking five percent less often.

Despite losing Pruitt in order to keep Davontae Harris (since placed on the practice squad after being activated from injured reserve) and Dontae Johnson, Woerner has finally come into his own, and has been used in very similar to ways that Pruitt has been in Tennesee, and with similar effectiveness. His 75.7 overall PFF grade ranks 16th to Pruitt’s 8th-ranked 79.9 rating.

What San Francisco should do now, given Woerner’s improved productivity, is find a few snaps per game to get Kittle off the field and give them to Woerner, especially in the first half, when it’s more affordable for Kittle to be off the field. They should also look to incorporate more two tight end sets, which is something that Shanahan wanted to accomplish last year with Kittle and Jordan Reed; neither stayed healthy at the same time for that to happen.

This isn’t asking Kittle to change the type of player he is, just for the 49ers to lessen the load on his shoulders, ever so slightly, over an extended period, so he can continue to be the player he is. With the addition of a 17th game, too, there might be a more pressing need for teams and players to pace themselves.

Managing tight end snaps might not be the norm, but neither is Kittle’s usage. He is going to make a nearly fully guaranteed $16.1 million salary in 2022, and a mostly guaranteed $16.3 million in 2023.

If the 49ers want to protect that investment, they should be more proactive about finding opportunities to get Kittle off the field, and ease his burden in every aspect of the offense.